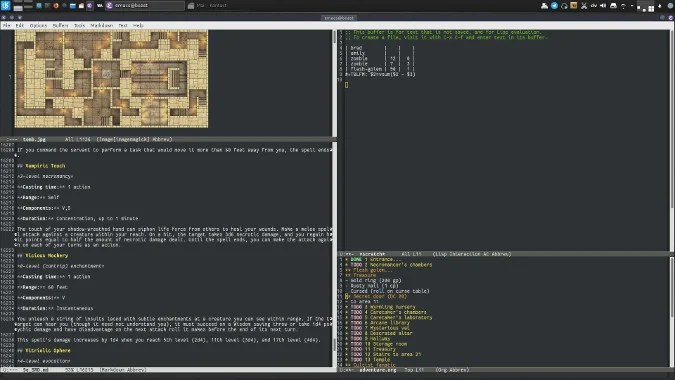

There are two ways to play a tabletop role-playing game (RPG): You can play an adventure written by the game's publisher or an independent author, or you can play an adventure that is made up as you go. Regardless of which you choose, there's probably prep work to do. One player (generically called the game master) must gather monster or enemy stats, loot tables, and references for rules, and the other players must build characters and apportion (pretend) equipment. Nothing's going to eliminate prep work from a complex RPG, but if you're an Emacs user, you might find that Emacs makes a great dashboard to keep everything all straight.

Organize the rules

Unfortunately, the digital editions of many RPGs are distributed as PDFs because that's what the RPG publisher sent to the printer for the physical edition. PDFs are good at preserving layout, but they're far from an ideal eBook format. If you play RPGs published under an open license, you can often obtain the rules in alternate formats (such as HTML), which gives you more control and flexibility. Even the world's first and most famous RPG, Dungeons & Dragons, provides its rules as a free download in digital format (which has been translated into HTML and Markdown by many a website).

I open the rules as Markdown in Emacs so that I have a searchable reference at the ready. While opening the rules as a PDF in a PDF reader lets you search for embedded text, using a text file instead provides several benefits. First of all, a text file is much smaller than a PDF, so it's faster to load and to search. Second, text files are easily editable, so if you find a rule that sends you seeking clarification, you can add what you learn (or whatever you make up) directly into your master document. You can also add house rules and additional resources. My aim is to have a single file that contains all of the rules and resources I use in games I run, with everything a quick Ctrl+s (C-s in Emacs notation) away.

Manage initiatives

Most RPG systems feature a method to determine the order of play during combat. This is commonly called initiative, and it comes up a lot since the source of conflict in games often involves combat or some kind of opposed competitive action. It's not that hard to keep track of combat with pencil and paper, but in games where I'm using digital assets anyway, I find it easier to stay digital for everything. Luckily, the venerable Org mode provides an excellent solution.

When players roll for initiative, I type their names into Emacs' scratch buffer. Then I type each monster or enemy, along with the hit or health points (HP) of each, followed by two columns of 0:

brad

emily

zombie 22 0 0

zombie 22 0 0

flesh-golem 93 0 0Then I select the block of player characters (PCs) and monsters and use the org-table-create-or-convert-from-region function to create an Org mode table around it. Using Alt+Down arrow (M-down in Emacs notation), I move each PC or monster into the correct initiative order.

| emily | | | |

| flesh-golem | 93 | 0 | 0 |

| zombie | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| brad | | | |

| zombie | 22 | 0 | 0 |During combat, I only need to record damage for monsters, because the players manage their own HP. For the enemies I control in combat, the second column is its HP (its starting number is taken from the RPG system's rules), and the third is the damage dealt during the current round.

Table formulas in Org mode are defined on a special TBLFM line at the end of the table. If you've used any computerized spreadsheet for anything, Org table will be fairly intuitive. For combat tracking, I want the third column to be subtracted from the second. Columns are indexed from left to right ($1 for the first, $2 for the second, and $3 for the third), so to replace the contents of column $2 with the sum of columns $2 and $3, I add this line to the bottom of the table:

#+TBLFM: $2=vsum($2 - $3)I don't actually type that into Emacs every time the game enters combat mode. Instead, I've defined an auto-completion trigger with Emacs' abbrev mode, a system that allows you to type in a special string of your choosing, which Emacs expands into something more complex. I define my abbreviations in a file called ~/.emacs.d/abbrev_defs, using rpgi followed by a Space as the trigger for Emacs to change the line to my initiative table formula:

(define-abbrev-table 'global-abbrev-table

'(

("rpgi" "#+TBLFM: $2=vsum($2 - $3)" nil 0)

))Each time a player deals damage to a monster, I enter the amount of damage in the damage column. To trigger a table recalculation, I press Ctrl+u Ctrl+c (i.e., C-u C-c in Emacs) or Ctrl+c Ctrl+c (i.e., C-c C-c) if I happen to be on the formula line:

| brad | | |

| emily | | |

| zombie | 12 | 10 |

| zombie | 15 | 7 |

| flesh-golem | 91 | 2 |

#+TBLFM: $2=vsum($2 - $3)This system isn't perfect. Character names can't contain any spaces because Org table splits cells by white space. It's relatively easy to forget that you processed one line and accidentally reprocess it at the end of a round. To add HP back to a creature's total, you have to use a negative number. (I think of it as negative damage, which suggests health.) Then again, many computerized initiative trackers suffer the same problems, so it's not a particularly bad solution. For me, it's one of the faster methods I've found (I'm happy to admit that MapTool is the best, but I use my Emacs workflow when I'm not using a digital shared map).

View PDFs in DocView

Sometimes a PDF is unavoidable. Whether it's a d100 list of tavern names or a dungeon map, some resources exist only as a PDF with no extractable text data. In these cases, Emacs' DocView package can help. DocView is a mode that loads PDF data and generates a PNG file for you to view (Emacs can also view JPEG files). I've found that large PDFs are problematic and slow, but if it's a low-resolution PDF with just one or two pages, DocView is an easy way to reference a document without leaving Emacs.

I use this mode exclusively for maps, tables, and lists. It's not useful for anything that might involve searching, because text data isn't accessible, but it's an amazingly useful feature for documents you only need to glance at.

The Ghostscript suite that ships with most Linux distributions (or certainly is available in your repository) allows you to process PDFs, drastically simplifying them by lowering the resolution of images from print quality to screen quality. The command contains mostly PostScript commands and attributes, but you don't need to become a PostScript expert to perform a quick down-res:

$ gs -sDEVICE=pdfwrite -dCompatibilityLevel=1.4 \

-dPDFSETTINGS=/ebook -dNOPAUSE -dBATCH \

-sOutputFile=adventure.pdf \

-dDownsampleColorImages=true \

-dColorImageResolution=72 big-adventure-module.pdfOpening PDFs in Emacs isn't as exciting as it may sound. It's not by any means a first-class PDF viewer, but for select resources, it can be a convenient way to keep all your information on one screen.

Create adventure rap sheets

Published adventures are often heavy on prose. The theory is that you've paid a lot of money for a prepared adventure, so you obviously want value for your purchase. I do value the lore and world-building that authors put into their adventures, but during a game, I like to have a quick reference to the information I need for the game mechanics to work as intended. In other words, I don't need to have the story of why a trap was placed in a dungeon when a rogue triggers it; I only need to know that the trap exists and what the rogue needs to roll in order to survive.

I haven't found any modern adventure format that provides me with just that information, so I end up creating my own "rap sheets": a minimal outline for the adventure, with just the game mechanics information I need for each location. Once again, Org mode is the best way for me to keep this information handy.

In Org mode, you create lists using asterisks for bullet points. For a sub-item, add an asterisk. Even better, press C-c t (that's Ctrl+c and then the t key) to mark the item as a TODO item. When your players clear an area in the game, press C-c t again to mark the location DONE.

* DONE 1 Entrance

** Zombie

AC 9 | HP 22

* TODO 2 Necromancer's chambers

** Flesh golem

AC 16 | HP 93

** Treasure

- Gold ring (200 gp)

- Rusty nail (1 cp)

Cursed (roll on curse table)

** Secret door (DC 20)

- to area 11Each asterisk is collapsible, so you can get a summary of a global area by collapsing your list down to just the top-level:

* DONE 1 Entrance

* TODO 2 Necromancer's chambers

* TODO 3 Wyrmling nursery

* TODO 4 Caretaker's chambers

* TODO 5 Caretaker's laboratoryAn added bonus: I find that making my own rap sheets helps me internalize both the mechanics and the lore of the adventure I'm preparing, so the benefits to this method are numerous. Since I manage any adventure I run in Emacs with Git, once I do the prep work for an adventure, I have fresh copies of all my assets in case I run the adventure with another group or with a set of fresh characters.

Make your own adventure journal

Generally, I let my players keep their own notes about the adventure because I want to encourage players to interpret the events happening in the adventure for themselves. However, a game master needs private notes to keep all of the improvised data in order. For example, if a published adventure doesn't feature a blacksmith shop, but players decide to visit a blacksmith, then a blacksmith needs to be invented in the moment. If the players revisit the blacksmith six weeks later, then they expect it to be the same blacksmith, and it's up to the game master to keep track of such additions to the published setting. I manage my personal notes about adventures in two different ways, depending on what's available to me.

If I have the text of the adventure in an editable format (such as HTML or Markdown), I enter my additions into the adventure as if the publisher had included them from the start. This means there's always one source of truth for the setting and for significant events.

If I haven't been able to get an editable copy of the adventure because it's a hard copy or a PDF that's not easily modified, then I write my additions into my rap sheets in Org mode. This functionally means that there's still one source of truth because my rap sheets are the first place I look for information, falling back on the published text only for details I've forgotten. Sometimes I like my additions enough to merge them back into my Git master for the adventure, but usually, I trust in improvisation and let additions happen dynamically for each group that plays the adventure.

Why Emacs is my favorite RPG dashboard

I've fallen into using Emacs for RPGs because it serves as the heads-up display of my dreams. The "right" answer is probably a good tiling window manager, but until I implement that, I'm happy with Emacs. Everything's bound to keyboard shortcuts designed for specificity and speed, and there's just enough easy customization that I can hack together good-enough solutions—sometimes even while players are arguing with one another about what to do next.

I've tried juggling multiple desktops, several PDF reader windows, and a spreadsheet for initiatives; while it's a fine experience, nothing has equaled the fluidity of Emacs as my RPG dashboard.

Hey! do you love Emacs? Write an article about how you use an Emacs (GNU or otherwise) for inclusion in our forthcoming Emacs series!

13 Comments