When you work with Kubernetes, it slowly becomes your production temple. You invest time and resources into developing and nurturing it, and you naturally begin looking for ways to control the Kubernetes end user in your organization. What can it do? What resources can it create? Can it label two deployments in a specific way? Which best practices should we follow?

Meet OPA Gatekeeper. This article will show you how to use it to create and enforce policies and governance for your Kubernetes clusters so the resources you apply comply with that policy.

(Noaa Barki, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Why use OPA Gatekeeper?

OPA Gatekeeper provides you with two critical abilities:

- Control what the end user can do on the cluster

- Enforce company policies in the cluster

However, the true power of Gatekeeper is its effect on organizations. Gatekeeper helps reduce the dependency between DevOps admins and the developers themselves. Enforcement of your organization's policies can be automated, which frees DevOps engineers from worrying about developers making mistakes. It also provides developers with instant feedback about what went wrong and what they need to change.

OPA Gatekeeper, a subproject of Open Policy Agent, is specifically designed to implement OPA into a Kubernetes cluster. (Fun fact: The project is a collaboration between Google, Microsoft, Red Hat, and Styra.) This article requires a basic understanding of both Kubernetes and OPA, so if you're already familiar with OPA, feel free to skip this part and move forward to the next one.

What is OPA?

OPA is like a super engine. You can write all your policies in it, then execute it with each input to check whether it violates any policies and, if so, in what way.

The main idea behind OPA is the ability to decouple the policy decision-making logic from the policy-enforcement usage.

Suppose you work in multiservices architecture. You might have to make policy decisions, for example, when that microservice receives an API request (like authorization). That logic is based on predicted rules in your organization, so in this case, you can offload and unify all your decision-making logic to a dedicated service: OPA.

How to use OPA:

- Integrate with OPA: If your services are written in Go, you can embed OPA as a package within your project. Otherwise, you can deploy OPA as a host-level daemon.

- Write and store your policies: To define your policies in OPA, you need to write them in Rego and send them to OPA. This way, whenever you use OPA for policy enforcement, OPA will query the input against these policies.

- Request policy evaluation: When your application needs to make a policy decision, it will send an API query request using JSON, containing all the required data via HTTP.

If you want to read more about OPA and how to use it, and learn more about its capabilities, I recommend reading OPA's documentation.

Kubernetes admission webhooks

Before we dive into how Gatekeeper works under the hood, we first need to learn about Kubernetes admission webhooks.

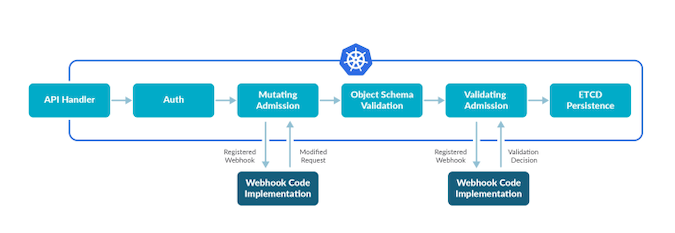

When a request comes into the Kubernetes API, it passes through a series of steps before it's executed.

- The request is authenticated and authorized.

- The request is processed by a list of special Kubernetes webhooks collections called admission controllers that can mutate, modify, and validate the objects in the request.

- The request is persisted into etcd to be executed.

Kubernetes admission controllers are the cluster's middleware. They control what can proceed into the cluster. Admission controllers manage deployments requesting too many resources, enforce pod security policies, and even block vulnerable images from being deployed.

Under the hood of an admission controller is a collection of predefined HTTP callbacks (i.e., webhooks), which intercept the Kubernetes API and process requests after they have been authenticated and authorized.

There are two types of admission controllers:

MutatingAdmissionWebhookValidatingAdmissionWebhook

Mutating admission controllers are invoked first, because their job is to enforce custom defaults and, if necessary, to modify the objects sent to the API server. After all modifications are completed and the incoming object has been validated, the validating admission controllers are invoked and can reject requests to enforce custom policies. Note that some controllers are both validating and mutating. If one of these rejects the request, the request will fail.

It's powerful, free and you might already use it

Several admission controllers come preconfigured out of the box, and you probably already use them. LimitRanger, for example, is an admission webhook that prevents pods from running if the cluster is out of resources. For further reading about MutatingAdmissionWebhook, see "Diving into Kubernetes MutatingAdmissionWebhooks" on the IBM Cloud blog.

(Noaa Barki, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Dynamic admission control

You might wonder why admission controllers are implemented with webhooks. This is where the admission controller shines and where the dynamic admission control comes in.

Webhooks give developers the freedom and flexibility to customize the admission logic to actions like Create, Update, or Delete on any resource. This is extremely useful, because almost every organization will need to add/adjust its policies and best practices.

Key issues arise from the way admission controllers operate. Modifying admission controllers requires them to be recompiled into Kube-apiserver, and they can only be enabled when the apiserver is activated. Implementing admission controllers with webhooks allows administrators to create customized webhooks and add mutating or validating admission webhooks to the admission webhook chain without recompiling them. The Kubernetes apiserver executes registered webhooks, which are standard interfaces.

For further reading about dynamic admission control, I recommend the K8s docs.

How OPA Gatekeeper works

Gatekeeper acts as a bridge between the Kubernetes API server and OPA. In practice, this means that Gatekeeper checks every request that comes into the cluster to see if it violates any of the predefined policies. If so, apiserver will reject it.

Under the hood, Gatekeeper integrates with Kubernetes using the dynamic admission control API and is installed as a customizable ValidatingAdmission webhook. Once it's installed, the apiserver triggers it whenever a resource in the cluster is created, updated, or deleted.

Since Gatekeeper operates through OPA, all policies must be written in Rego. Fortunately, Kubernetes has that covered by using the OPA Constraints Framework.

A constraint is a CRD representing the policy we want to enforce on a specific kind of resource. When the ValidatingAdmission controller is invoked, the Gatekeeper webhook evaluates all constraints and sends OPA the request together with the policy to enforce it. All constraints are evaluated as logical, and if a constraint is not satisfied, the whole request is rejected.

How to use OPA Gatekeeper: a simple scenario

Suppose you want to enforce a resource without an owner label.

First, Install Gatekeeper on your cluster:

kubectl apply -f

https://raw.githubusercontent.com/open-policy-agent/gatekeeper \

/release-3.4/deploy/gatekeeper.yamlYou can test it by running the following command:

kubectl get pods --all-namespaces

If everything works correctly, you should see a running pod named gatekeeper-controller-managerunder gatekeeper-systemnamespace.

Apply the ConstraintTemplate that will require all the labels described by the constraint to be present:

apiVersion: templates.gatekeeper.sh/v1beta1

kind: ConstraintTemplate

metadata:

name: k8srequiredlabels

spec:

crd:

spec:

names:

kind: K8sRequiredLabels

validation:

# Schema for the `parameters` field

openAPIV3Schema:

properties:

labels:

type: array

items: string

targets:

- target: admission.k8s.gatekeeper.sh

rego: |

package k8srequiredlabels

violation[{"msg": msg, "details": {"missing_labels": missing}}] {

provided := {label | input.review.object.metadata.labels[label]}

required := {label | label := input.parameters.labels[_]}

missing := required - provided

count(missing) > 0

msg := sprintf("you must provide labels: %v", [missing])

}Apply the constraint that will use the K8sRequiredLabel you created before you scoped to namespace, so every namespace will be forced to have an owner label:

apiVersion: constraints.gatekeeper.sh/v1beta1

kind: K8sRequiredLabels

metadata:

name: ns-must-have-owner

spec:

match:

kinds:

- apiGroups: [""]

kinds: ["Namespace"]

parameters:

labels: ["owner"]

Audits

As I like to say, the cluster is your production temple, so you want ongoing monitoring to detect the remediation of preexisting misconfigurations. This is where the audit comes in.

When the Gatekeeper webhook is invoked, it stores audit results as violations in the status field of the relevant constraint. For example:

apiVersion: constraints.gatekeeper.sh/v1beta1

kind: K8sRequiredLabels

metadata:

name: ns-must-have-owner

spec:

match:

kinds:

- apiGroups: [""]

kinds: ["Namespace"]

parameters:

labels: ["owner"]

status:

auditTimestamp: "2019-08-06T01:46:13Z"

byPod:

- enforced: true

id: gatekeeper-controller-manager-0

violations:

- enforcementAction: deny

kind: Namespace

message: 'you must provide labels: {"hr"}'

name: default

- enforcementAction: deny

kind: Namespace

message: 'you must provide labels: {"hr"}'

name: gatekeeper-system

- enforcementAction: deny

kind: Namespace

message: 'you must provide labels: {"hr"}'

name: kube-public

- enforcementAction: deny

kind: Namespace

message: 'you must provide labels: {"hr"}'

name: kube-system

Maybe you want to create a policy that enforces all ingress hostnames to be unique. In this case, you would want to use the audit feature. However, the constraint that enforces a unique ingress hostname must have access to all ingresses other than the object under evaluation. This situations requires data replication into OPA.

A simple scenario

By default, an audit does not require replication, but there are two ways to configure data replication manually:

- Use the OPA cache mechanism: Set the flag

audit-from-cacheto true, which will enable the OPA cache to be used as the source of truth for all audit queries. Any object must first be cached before it can be audited for constraint violations. - Use a Kubernetes

configresource: Create aconfigresource and define the resources you want to be replicated into OPA insyncOnly. Don't worry, updatingsyncOnlyshould dynamically update all synced objects.

For example, the following configuration replicates all namespace and pod resources to OPA:

apiVersion: config.gatekeeper.sh/v1alpha1

kind: Config

metadata:

name: config

namespace: "gatekeeper-system"

spec:

sync:

syncOnly:

- group: ""

version: "v1"

kind: "Namespace"

- group: ""

version: "v1"

kind: "Pod"Dry Run

You can take it even further and test the constraints before adding and enforcing them. This is where the dry run feature comes in.

Dry run provides the same functionality as audit, enabling you to deploy the constraints and see all constraint violations reported in the status without making actual changes. To configure a constraint for dry run mode, all you need to do is use the enforcementAction: dryrun label in the constraint's spec. By default, enforcementAction is set to "deny," as the default behavior is to deny admission requests with any violation.

For example:

apiVersion: constraints.gatekeeper.sh/v1beta1

kind: K8sRequiredLabels

metadata:

name: ns-must-have-owner

spec:

match:

kinds:

- apiGroups: [""]

kinds: ["Namespace"]

parameters:

labels: ["owner"]

status:

auditTimestamp: "2019-08-06T01:46:13Z"

byPod:

- enforced: true

id: gatekeeper-controller-manager-0

violations:

- enforcementAction: dryrun

kind: Namespace

message: 'you must provide labels: {"hr"}'

name: default

- enforcementAction: deny

kind: Namespace

message: 'you must provide labels: {"hr"}'

name: gatekeeper-system

- enforcementAction: deny

kind: Namespace

message: 'you must provide labels: {"hr"}'

name: kube-public

- enforcementAction: deny

kind: Namespace

message: 'you must provide labels: {"hr"}'

name: kube-systemThink big

Now that your production is safe and sound, I'd like to pause for a second and ask you a question: How is Gatekeeper different from unit tests? Personally, when I first heard about Gatekeeper, I couldn't understand, "Why does it have to be only about the production?" After all, ideally, doesn't it all go through the same pipeline?

As a developer, thinking about Kubernetes policies as if they were unit tests made so much sense that it got me wondering, what's the difference between my code and Kubernetes resources?

Enter Datree.

Datree is a command-line interface (CLI) solution that enables you to test policies against YAML files. The CLI comes with built-in policies for all Kubernetes best practices and a centralized management solution for any policies you create. Run Datree in the CI, or as a precommit hook, and use it as you would use a local testing library. It's an open source project, so it's free. You can find the project on GitHub and get all the info on Datree's website.

I encourage you to review our code and give us your feedback so it can be the best solution for your production.

Summary

The way I see it, just because Kubernetes allows you to deploy a pod with access to the host network namespace, for example, doesn't mean it's a good idea.

When you adopt Kubernetes, you're also changing the culture of your organization. DevOps is not something that happens overnight; it's a process, and it's important to know how to manage it, especially in terms of scale.

I hope this will inspire you to start thinking about your policies and how to enforce them within your organization.

This article originally appeared on Datree's blog and is republished with permission.

Comments are closed.