It's pretty well known that Linux is a big deal in modern movie making. Linux is the standard base, a literal industry standard for digital effects but, like all technology with momentum, it seems that the process of cutting footage still defaults mostly to a non-Linux platform. Slowly, however, as artists seek to simplify and consolidate the post-production pipeline, Linux video editing is gaining in popularity.

It can be difficult to talk about video editing objectively because it means so many different things to different people. For instance, to some people a video editing application must be able to generate fancy animated title sequences, while professional users balk at the idea of doing serious work on titles in their video editor. It's not unlike the debate over professional SLR cameras that happened when digital cameras in phones became contenders for serious photography.

For this reason, a pragmatic overview of a Linux-based video editor needs two broad qualifiers: How it performs for home users, and how it might integrate into a professional pipeline.

Defining key terms

- Independent: For the purposes of this article, I'll call a workflow that begins and ends with either one video editing software or one computer system either "independent" or "hobbyist." In other words, an independent or hobbyist filmmaker is likely to use one application to do video editing, maybe a few other applications for specialized tasks like audio sweetening or motion graphics, and then they're done. Their project is exported and delivered.

- Professional integration: A "professional" editor probably also uses only one application to edit video, but that's because they're a cog in a larger machine. A professional editor might get their footage from a producer or director, and when they're done they probably aren't exporting the final version that their audiences are going to see, but they'll pass their work on to audio engineers, VFX artists, and colorists.

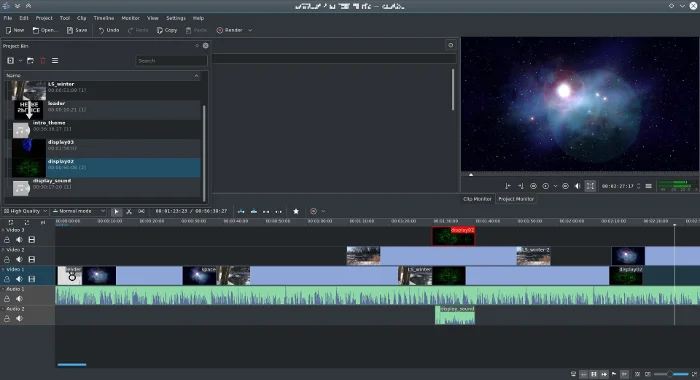

Top pro pick: Kdenlive

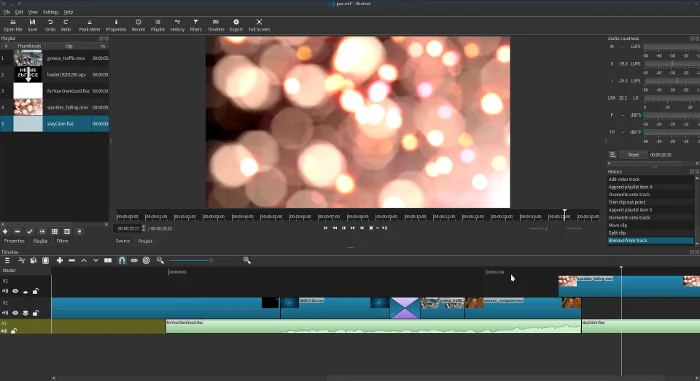

Kdenlive is the best-in-class professional open source editing application, hands-down. As long as you run a stable version of Kdenlive on a stable Linux OS, use reasonable file formats, and keep your work organized, you'll have a reliable, professional-quality editing experience.

opensource.com

Strengths

- The interface is intuitive for anyone who has ever used a professional-style editing application.

- The way you work in Kdenlive is natural and flexible, allowing you to use both of the major styles of editing: cutting by numbers and just mousing around in the timeline.

- Kdenlive has plenty of capabilities beyond just cutting up footage. It can do some advanced visual effects, like masking, all manner of composting (see this, this, and this), color correction, offline "proxy" editing, and much much more.

Weaknesses

- The greatest weakness of open source editing is also its greatest strengths: Kdenlive lets you throw nearly anything you want at it, even if that sometimes means its performance suffers. You should resist the urge to take advantage of this flexibility and instead manage your assets and formats smartly. Instead of using an MP3, convert the MP3 to WAV first (which is what other editors do for you, but they do it "behind the scenes"). Don't throw in an animated GIF without first breaking it out into a series of images. And so on. Gaining flexibility means you gain the responsibility for maintaining a sensible media library.

- The interface, while accounting for both "traditional" editing styles and the "modern" style of treating the timeline as a sort of scratchpad, wouldn't really satisfy an editor who wants to cut by numbers. Currently, there's no way, for instance, to modify or move clips with quick number-pad entries (typing +6, for instance, has no effect on a video region's placement in the timeline).

Independent

- If anything, Kdenlive could be overkill for home users who aren't accustomed to professional-style editing. Basic operations of the interface are mostly intuitive, but new editors might feel that there's a learning curve for advanced operations (like layered composting and offline editing).

- On the other hand, it scales down well. You can use a fraction of its features and find it a pretty simple, mostly intuitive editor.

- And for serious home editors and independent movie makers, Kdenlive is worth learning and using, and it is likely to satisfy all requirements. It may not always be a drop-in replacement if you're transitioning from some other editor, but it's familiar enough to keep the learning curve manageable.

Professional integration

- If you're working in a production environment with an established workflow, then any change to your editor requires adaptation.

- Kdenlive saves projects as an XML file, so it's possible to convert an existing edit decision list (EDL) to a Kdenlive project file, although there aren't any official auto-converters available yet, so round trips (i.e., returning to the original application) out of Kdenlive would require intervention. Alternately, round trips can be done with lossless clip exports, which can be reintegrated into a project after whatever has been applied from the external application.

- The same holds true for audio. You can render audio to a file and import into an external digital audio workstation (DAW), but currently there's no native, built-in audio-export target for popular formats like Open Media Framework (OMF).

- For the most part, as long as your pipeline isn't perilously rigid, Kdenlive can exist within any professional environment. It can output video, audio, and image sequences, and it's hard to imagine a workflow where such generic output isn't acceptable.

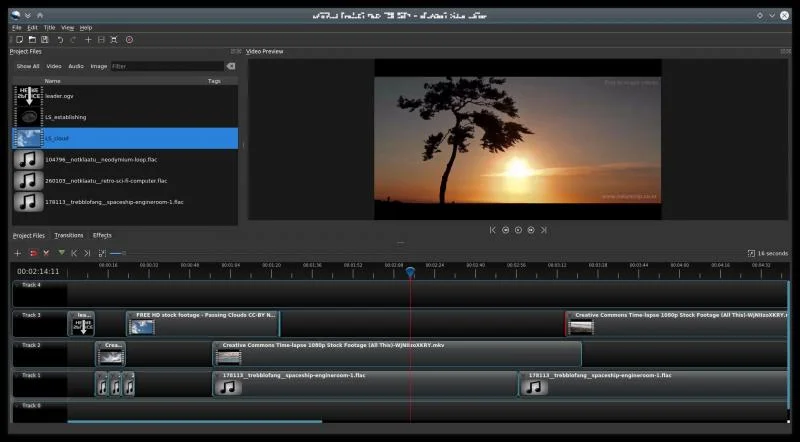

Hobbyist pick: OpenShot

OpenShot is a simple but robust video editor. If you're not interested in learning the finer details on how to edit video, then OpenShot is for you. It doesn't scale up; a professional editor will find it restrictive, but for a quick and easy edit, OpenShot is a great choice on any OS.

Strengths

- OpenShot is focused. It understands exactly what its audience wants: the ability to make attractive videos with minimal fuss. Its interface is intuitive, and what you can't immediately figure out from context, you can access with a right-click.

- The most common transition, a crossfade, is available by overlapping the edges of two clips. This is such a simple and obvious trick, but it cuts down on so many mouse clicks that you'll wonder why all video editors don't do that.

- It's also a very conservative application. You won't see a new OpenShot release every month, and that's a good thing. You can download OpenShot as an AppImage today and use it for the next year or more. It's a beautiful, comfortable, simple piece of software.

Weaknesses

- A hobbyist's strengths are a pro's weaknesses. It's a deliberately simplified system, and little conveniences like the auto-crossfades are unwelcome to a professional editor who doesn't necessarily want clips to crossfade when they overlap.

- OpenShot doesn't have a very robust engine for real-time effects. Too many dynamic effects severely slow playback.

Independent

- An independent or hobbyist editor with simple needs will find OpenShot perfect. It's an easy install, it has all the usual benefits of open source multimedia (near indifference to codecs, no false limitations or paywalls for advanced features).

Professional integration

- Integrating OpenShot with a larger pipeline is possible, but only in the sense that it can output generic video and audio files and image sequences. Its project file format, however, is also open source, and it saves into a JSON format that theoretically could be leveraged for an EDL, but there's no built-in exporter for that.

Everything else

Kdenlive and OpenShot are my top picks, the open source editors an editor ought to turn to for a quick fix, but there are, of course, several others to look at.

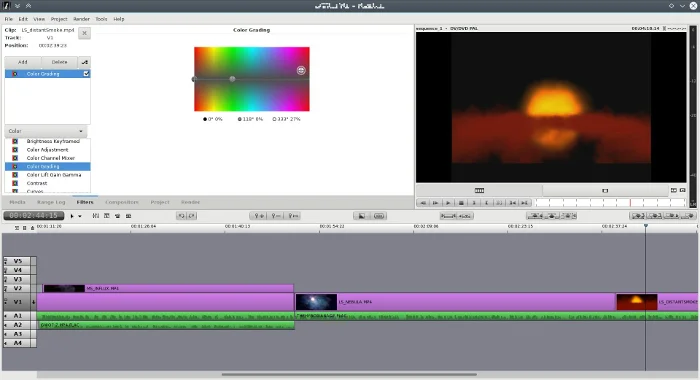

Flowblade

Flowblade is a simplified video editor that focuses on the editorial process. If you're an experienced editor and just want to get down to business, or you 're a hobbyist who needs little more than an interface to assemble video clips in sequence, then Flowblade's minimal interface may appeal to you.

opensource.com

Strengths

- A no-frills, stable application for quick, no-nonsense cutting.

- Its workflow favors a traditional cutting style: mark in, mark out, dump into timeline. Rinse and repeat.

- This makes it slightly less convenient to stumble around your project in search of a good edit, but that's what makes it so efficient and smooth when you know what you want.

- A professional-level editor who lives to count frames and edit on the keyboard will love Flowblade.

Weaknesses

- Flowblade's interface is arguably overly simple.

- At the time of this writing, its keyboard shortcuts are not user-definable (although it's written in Python, so an editor fluent in Python can adjust preferences by brute force).

Independent

- Many of the "obvious" things a hobbyist would expect from a video editor just don't happen in Flowblade. For instance, moving a clip once it's in the timeline requires activation of an "overwrite" mode, since otherwise clips "float" left.

Professional integration

- In addition to generic video and audio files, Flowblade can export to MLT XML for use with the open source multimedia framework that powers it, as well a plain text, parseable EDL. Additionally, Flowblade's project format is plain text and could be used to extract information for a custom EDL format.

- These options don't provide specialized hooks into specific applications, but it's certainly enough of a variety that a simple converter should be able to import the information.

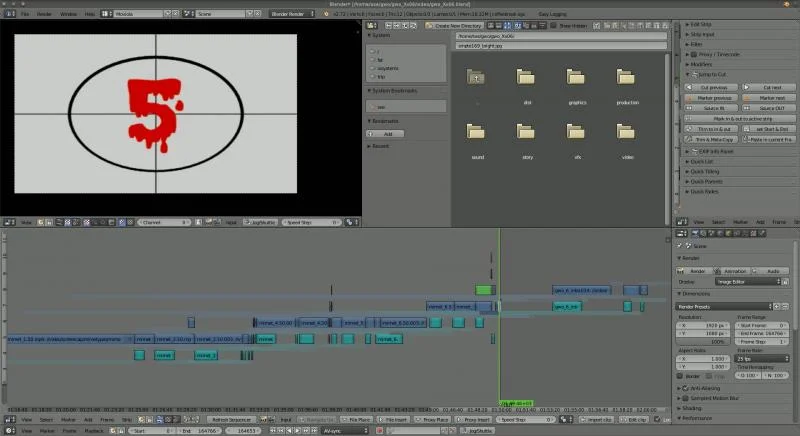

Blender

Blender excels at efficiency. Once you know how to interact with its interface, you can accomplish amazing things amazingly quickly. Transferring this kind of efficiency over to video editing is a dream come true.

Strengths

- By default, Blender's video sequence editor (VSE) is, from what I can tell, optimized for only the most basic "editing" tasks. This makes sense, given that in the animation and VFX world, there isn't generally excess footage. Artists work on shots that have already been finalized, so the only editing task after all the animation is done is to reintegrate shots into the final cut of the movie. Luckily, though, there are several plugins (such as Easy-Logging and the Blender Velvets) in active development to apply traditional editing interface conventions to Blender's VSE mode, and they manage to transform Blender into a very usable video editing software.

- Blender is stable, fully cross-platform, popular, and under steady development. Using it to edit video isn't exactly common, but the application as a framework for multimedia work is robust and reliable.

Weaknesses

- If you're expecting a traditional editing platform, Blender's weaknesses are many. Its interface can be confusing, and the UI is unconventional as a video editor, at best. Even with VSE plugins and personal customizations, the interface is mostly utilitarian.

- Blender's rendering engines are backends for 3D model rendering. Rendering a video sequence, especially with effects (like color correction, which one would expect to have on each clip in a primary editing application) applied to each clip, takes far longer (10x as long from Kdenlive and Flowblade, in my most recent tests) than rendering from any other video editor. This might be partly because the Blender interface offers no control over FFmpeg threads.

- The VSE lacks integration with the rest of Blender. You cannot, for instance, attach clips from your VSE edit into the node editor and apply fancy effects. In Blender's internal pipeline, the VSE is definitely a separate process.

Independent

- A hobbyist who knows nothing about Blender will find a steep learning curve. Even with VSE add-ons to make the VSE act more like a "normal" application, anything beyond basic cuts and sequencing just doesn't work the way most users would expect.

- Like all powerful applications, however, Blender is by all means worth knowing. In terms of application design, it's one of the best examples, outside of Emacs, of combining internal logic and consistency with endless extensibility to produce a powerful, unstoppable force of computational wonder.

Professional integration

- Depending on your industry, your production house may already be using Blender, if not for video editing then for animation or motion graphics.

- There are several EDL export add-ons available, and Blender's seamless integration with Python makes it trivial for a technically minded editor or support staff to export whatever information is necessary to blend Blender into any pipeline.

Shotcut

Shotcut is a video editor being developed by Dan Dennedy, an MLT co-founder and current project lead. It is designed from the ground up to be cross-platform and leverages new technologies like WebVfx (visual effects created with web technologies) and Movit (GPU image processing).

opensource.com

Strengths

- Shotcut is using the latest in open source technology to provide performance unlike any other open source video editor. Its real-time effects are smooth as is, and they will get even better once it's offloaded onto the GPU.

- The interface is mostly familiar, although some liberties are taken in the interest of progress. One wonders if mobile devices are on the roadmap, because much of the interface design would work well on a tablet or a large phone screen.

- Shotcut is JACK-aware, so tethering it to a pro audio application like Ardour is trivial.

Weaknesses

- Shotcut is a little progressive, so there's a learning curve involved where its interface implements something different than the de facto standard. For instance, the workflow in a traditional editor is: bring a clip into your bin, open that clip from the bin, mark in and out, and put it in the timeline. With Shotcut, however, there's no internal import process to populate your bin ("playlist," in Shotcut terminology). You can either drag and drop from your file manager or you can open a clip and add that clip to your playlist, or you can bypass the playlist entirely and just add it to your timeline.

- It's less esoteric, for example, there's no way to group select several clips in the timeline to move them. You can insert clips in front of them, but editors used to using their timeline as a scratchpad with lots of groups of edited scenes might find this limitation troublesome.

- The effect stack is still a work in progress. Important effects, like a chromakey (green screen), are missing. They're being added as the dev team perfects their interfaces and functionality.

Independent

- For basic editing, Shotcut is a breeze. It's uncluttered, relatively lightweight, and functional. It's got everything you need and doesn't offer a lot of options you probably don't intend to use.

- In its current state, it doesn't scale up. When you hit its ceiling, you'll have to move to another application. For some, this might be when they suddenly realize they need to do complex composites (to be fair, it's arguable that complex composites shouldn't be done in a video editing application at all, but that doesn't change expectations), while for others it will be small interface preferences, like Shotcut's inability to dynamically create a new audio track when dragging an audio-only clip into a timeline with only one video track.

Professional integration

- Shotcut isn't production-ready yet, but since a true professional is more than the sum of the tools, it could be used in a professional setting. Shotcut can export an EDL, and it stores its project files as MLT XML, so you could extract information for a custom EDL format as needed.

Non-open editors

There's a handful of cross-platform editors that are not open source. However, they can run on an otherwise open stack (in other words, they are fully Linux-compatible), which is a pretty common paradigm in the professional film world.

A not insignificant advantage to these closed-source solutions is that a team of editors can use the same software regardless of the OS they're running.

Lightworks

A long-time editing solution in Hollywood, Lightworks is now free to download. While its natural approach to editing defers to a traditional film workflow, working in the timeline is possible and new features are constantly being added to make sandboxing in the timeline comfortable. The free version is basically a complete solution for serious editng, but if you pay for a subscription you "unlock" better codec support and a few effects (which are, awkwardly, not cross-platform).

Strengths

- Nobody would call Lightworks the industry standard, but it is an Emmy award winner and has a long history of professional use before it became no-cost software independent of its hardware stack. It's a robust application with some serious pro features, such as timeline effects, codec support, lots of export formats, and a unique but efficient interface.

- It's a technical editing environment. It's very aware of editing decisions and timecode and frame numbers, so if you are a professional editor who needs to know that your edit can conform later in the pipeline, Lightworks won't let you down.

- Real-time effects are well supported in Lightworks, so performance is as good as your system specs provide.

Weaknesses

- It's not open source. Its development team announced many years ago that the code would be released in Q3 of 2012; now the official stance in the forums is that "Lightworks is freemium software."

- Furthermore, Lightworks is not a lightweight application. It expects a powerful rig, and at a certain point, it bottoms out and just plain won't run.

- Lightworks' default editing style in many ways mimics the traditional film-editing process. Its timeline is designed for keyboard and shuttle control. Hobbyists or editors who were trained to do their editing with the mouse might find Lightworks a little difficult to get used to. With each new version, the timeline gets a little more mouse-friendly, but the overall design is somewhat technical.

Independent

- Lightworks is probably overkill for the hobbyist. It works well, but there's a learning curve and an emphasis on precision and professionalism that will probably get in the way for people who just want to edit.

Professional integration

- Lightworks exports to a number of formats, such as OMF and AAF, so it's prepared to communicate with whatever's next in your pipeline. If it doesn't export to what you need, it does export to a variety of video and audio formats.

Da Vinci Resolve

Coming from Da Vinci's color correction suite, and once tied to a proprietary hardware suite, Resolve is a cross-platform editor distributed for $0.

Strengths

- Da Vinci has been an industry standard for decades, and while Resolve is technically relatively new, many professionals in the industry have some familiarity with the system in general.

Weaknesses

- Resolve, like Lightworks, has hefty hardware requirements. If your system doesn't meet its requirements, it doesn't run. There's no lightweight mode, even if you just want to do some basic edits.

- Resolve is not open source.

Independent

- Resolve is probably overkill for hobbyists, but its interface is flexible and allows for several editing styles. Its interface is fairly intuitive; if you've used a video-editing application before, you can probably figure out Resolve with an afternoon and a few online tutorial videos.

Professional integration

- Da Vinci exports to several exchange formats as well as video, audio, and image sequences.

Hiero

Hiero isn't, strictly speaking, a video editor, but a show viewer. However, it's set up such that clips can be arranged and adjusted, so it sometimes gets used as a video editing solution by artists familiar with other Foundry tools.

All the rest

Of course, there are still more options. Some, like Pitivi and Cinelerra, are less active and less stable now than they may have once been, others, like Avidemux, are limited in scope, and still others, like using FFmpeg directly, are just too niche to cover.

The point is that there are plenty of very good video editing solutions for Linux. All you have to do is choose one, and get creative.

23 Comments