Definition: RTFM (Read The F'ing Manual). Occasionally it is ironically rendered as Read The Fine Manual, a phrase uttered at people who have asked a question that we, the enlightened, feel is beneath our dignity to answer, but not beneath our dignity to use as an opportunity to squish a newbie's ego.

Have you noticed that the more frequently a particular open source community tells you to RTFM, the worse the FM is likely to be? I've been contemplating this for years, and have concluded that this is because patience and empathy are the basis of good documentation, much as they are the basis for being a decent person.

First, some disclaimers.

Although I've been doing open source documentation for almost 20 years, I have no actual training. There are some people that do, and there are some amazing books out there that you should read if you care about this stuff.

First, I'd recommend Conversation and Community, by Anne Gentle. And if you're looking for a conference about this stuff, there are two that I'd suggest: Write The Docs and OpenHelp.

The title of this essay comes from Kathy Sierra, who in a presentation years ago had a slide that said, "If you want them to RTFM, make a better FM." But how do we go about doing that?

There's common wisdom in the open source world: Everybody knows that the documentation is awful, that nobody wants to write it, and that this is just the way things are. But the truth is that there are lots of people who want to write the docs. We just make it too hard for them to participate. So they write articles on Stack Overflow, on their blogs, and on third-party forums. Although this can be good, it's also a great way for worst-practice solutions to bloom and gain momentum. Embracing these people and making them part of the official documentation effort for your project has many advantages.

Unlike writing fiction, where the prevailing advice is just start writing, when it comes to technical writing, you need to plan a bit. Before you start, there are several questions you should ask.

Who?

The first of these is who?. Who are you writing to? Some professional tech writers create personas so that when they are writing, they can think to themselves, "What would Monica need to know in this situation?" or "What kind of problem is Marcus likely to have around this topic?" and then write accordingly.

At this point in the process, remembering that not all of your audience consists of young, white, English-speaking men who grew up watching Monty Python is critical.

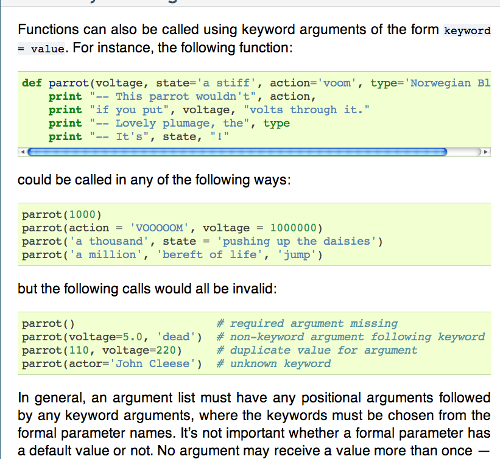

Exhibit A: Python documentation

Python documentation is riddled with Monty Python references:

Now, don't mistake me: Python documentation, is, for the most part, awesome. But there's one complaint I have with it—the inside jokes. The Monty Python humor runs through all of the documentation, and this is a double-edged sword. Inside jokes form a sense of community, because you get the joke, and so you're on the inside. Except when you're not. In which case, inside jokes point out starkly that you're not on the inside. Tread carefully here. Consider including a reference guide that explains the jokes, and, in the case of dead parrots, points to a YouTube video:

The same goes for colloquialisms.

Exhibit B: PHP documentation

In this example from the PHP docs, the English saying, finding a needle in a haystack, is referenced in an effort to make the example more understandable. If you are a native English speaker, the example is great because it makes obvious which argument is which. For readers who are not native English speakers, however, the example points out that they are not the target audience, which can have a chilling effect on bringing new people into your community.

Where?

The next question to ask is where?. Yes, you need to have documentation on your project website, but where else is the conversation already happening? Except in rare cases, other sites, such as StackOverflow, are the de facto documentation for your project. And if you care about actually helping your users, you need to go where they are. If they're asking questions on Twitter, Facebook, or AOL, you need to go there, answer their questions there, and give them pointers back to the official documentation so that they know where to look next time.

You can't control where people are having their conversations, and attempts to do so will be seen as being out of touch with your audience. (While I'm on the topic, they're not your audience, anyway.)

Once, when I worked for a former employer, we discovered that our audience was having their conversations on Facebook, rather than on our website. Those in power decided that we had to stop this, and we put up our own internal social site. And then we told everyone that they had to use it—instead of Facebook—when discussing our organization. I suspect you can guess how well that worked out for us.

But you're doing the same thing when you ignore the audience on StackOverflow, Twitter, and various third-party websites, because they're not in the right place.

What?

On to the mechanics. What should you be writing?

Scope

The first thing you must decide (and, yes, you need to decide this, because there's not necessarily one right answer) is what your document scope is. That is: What topics are you willing to cover? The implication, of course, is that everything else is out of scope, and should be pushed to someone else's documentation.

For example, on the Apache Web Server documentation, we have a document called Getting Started, which covers what you need to know before you get started. The goal of the document is to draw a line saying what is outside of the scope of the documentation, while also pointing people to resources that do in fact cover those things in great depth. Thus, the HTTP specification, the inner workings of DNS, and content matters (such as HTML and CSS) are firmly outside of the scope of the documentation, but everyone using the Apache Web Server needs to know these things.

Types of docs

Once you've determined the scope, and who you're writing to, there are several different kinds of documents that you can write for them. Anne Gentle categorizes them like this:

Start here

Like the Getting Started document I mentioned previously, this is the place where you tell users what they need to know before they even get started.

Reference guide

The reference guide is comprehensive and usually pretty dry. This is where terms are defined, functions' input and output are explained, and examples are given. The tone is factual and to the point. There's not much discussion, or conversation. The voice is usually impersonal.

Tutorials

Tutorials hold your hand and lead you down the path. They show you each step, and occasionally sit down on a bench by the path to explain the rationale for a particular step. They are very conversational, sometimes even chatty. The voice is personal; you are speaking to a particular person, defined in the earlier persona phase.

Learning/understanding

Often linked to from the tutorials, the learning/understanding documents dig deeper. They investigate the why and the how of a particular thing. Why was a certain decision made? How was it implemented in the code? What does the future look like for this thing? How can you help create that future? These documents are sometimes better done as blog posts than as part of the formal documentation, as they can be a serious distraction to people that are just trying to solve a problem.

Cookbook/recipe

There's a reason that the Cookbooks are often the best selling part of the O'Reilly technical book catalog. People want solutions, and they want them now. The recipe, or cookbook section of your document, should provide cut-and-paste best-practice solutions to common problems. They should be accompanied by an explanation, but you should understand that most of the cookbook users will cut and paste the solution, and that'll be the end of it for them.

A large part of your audience only cares about solving their immediate problem, because that's all they're getting paid to do, and you need to understand that this is a perfectly legitimate need. When you assemble your new Ikea desk, you don't care why a particular screw size was selected, you just want the instructions, and you expect them to work.

So it's critical that examples have been tested. No matter how trivial an example is, you must test it and make sure it does the expected thing. Many frustrating hours have been spent trying to figure out why an example in the docs doesn't work, when a few minutes of testing would have revealed that a colon should have been a semicolon.

Recipes should also promote the best practice, not merely the simplest or fastest solution. And never tell them how not to do it, because they'll just cut and paste that, and then be in a worse fix than when they started.

One of my favorite websites is There, I Fixed It, which showcases the ingenuity of people who solve problems without giving much thought to the possible ramifications of their solution—they just want to solve the problem.

Error messages

Yes, error messages are documentation, too. Helpful error messages that actually point to the solution save countless hours of hunting and frustration.

Consider these two error messages:

`ERROR. FORBIDDEN`

and

`Access forbidden by file permissions. (ERRNO 03425)`

The first is alarming, but unhelpful, and will require a great deal of poking around to figure out why it was forbidden. The second tells you that it has to do with file permissions, and has the added benefit of an error number that you can Google for the many articles that detail how to fix the problem.

Philosophy

This entire line of thought came out of years of enduring technical support channels—IRC, email, formal documentation, Usenet, and much more. We, those who hold the answers, seem to want to make it hard for the new person. After all, we walked uphill in the snow to school, and back, with bare feet, remember? We figure out how to make things work by reading the code and experimenting. Why should we make it any easier for these kids? They should be forced to earn it, same as we did, right?

The technology world is getting more complicated every day. The list of things that you're expected to know grows all the time, and nobody can be an expert in everything. Expecting that everyone do all of their homework and ask smart questions is not merely unreasonable, it's becoming impossible.

Compassionate tech support—and better documentation—is the only way for people to use your software effectively. And, if they can't get their answers in a reasonable amount of time, they'll use a different solution that has a better paved on-ramp.

In the first edition of his Programming Perl book, Larry Wall, creator of the Perl programming language and father of that community, joked about the three virtues of a programmer: laziness, impatience, and hubris:

The explanation of this joke is well worth reading, but keep in mind that these are the virtues of a programmer, in their role as a programmer, relating to a computer. In a 1999 book, Open Sources: Voices from the Open Source Revolution, Larry explained that as a person, relating to other people, the three virtues we should aspire to are: diligence, patience, and humility.

When we're helping people with technical problems, impatience is perceived as arrogance. "My time is more important than your problem." Hubris is perceived as belittling. And laziness? Well, that's just laziness.

Being patient and kind, helping people move at their own pace (even when it feels slow), is perceived as respect. Welcoming people at whatever level they are, and patiently helping them move up to the next level, is how you build your community.

Don't make people feel stupid: This must be a core goal.

Even if everyone else in the world is a jerk, you don't have to be.

Dish

This article is part of the Doc Dish column coordinated by Rikki Endsley. To contribute to this column, submit your story idea or contact us at open@opensource.com.

24 Comments